The Birth of Radar!

This is a re-post from my old 'Ratmobile Adventures' blog - which can still be found here! Hopefully it'll be the start of a few aviation history posts I might write as the mood takes me.

Greetings Fellow Adventurers!

It always amazes me what you can find by the side of the road. Our countryside is peppered with little plaques, memorials and notice boards, all giving an insight into the rich and varied history of our country, the events big and small that helped form it and the people who created it. There is one such memorial just off the A5 near Daventry. It marks the spot where, in February 1935, two men drove a Flatnose Morris van into a field near Upper Stowe in Northamptonshire. They erected two sets of wooden poles, rigged wires between them, connected them to some receiving equipment in the back of the van and set to work, and in doing so they changed the course of history.

The Memorial in question with some of the much needed hills behind it - read on

During the early 1930s, with the prospect of war growing ever greater, the Air Ministry became increasingly interested in applying science and technology to the defence of Britain from the threat of hostile aircraft. In November 1934, under the chair of Sir Henry Tizard, they formed the 'Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Defence', or the 'Tizard Committee' as it become known. It was tasked with reviewing all the current scientific knowledge and evaluating how it could be applied to issue of air defence.

Robert Watson-Watt

Robert Watson-Watt, a recognised expert in the field of radio propagation and the then superintendent of the Radio Research Station, along with his scientific assistant Arnold F. 'Skip' Wilkins, become involved with the Tizard committee when they were asked for their opinion of a newspaper article about a supposed German 'Death Ray'. They successfully disproved it, and whilst doing so also mentioned the subject of locating aircraft by the means of radio.

Following this, Wilkins, using Watson-Watt's previous work on detecting lightning strikes, developed a method whereby radio waves sent out from an appropriately powered transmitter would bounce off an aircraft in the air. Then using a receiver linked to an oscilloscope, the difference in strength between the reflected radio waves and the source transmission could be measured and used to calculate its position. On 12th February 1935, Watt detailed this method in a secret report sent to the Air ministry titled 'The Detection of Aircraft by Radio Methods'. They were asked to prove it, which is how the 'Daventry Experiment' came about.

Arnold F. 'Skip' Wilkins

The site where this experiment was carried out is marked by the 'Birth of Radar' memorial. The location was chosen by Watson-Watt and Wilkins for it's proximity to the BBC Daventry radio transmitter, but with enough hills in the way to reduce the strength of the transmission to the required levels. The initial set up took place on the 25th February and the final adjustments which, having taken longer then expected and due to the lack of lights in the van, Wilkins performed by match-light just before midnight.

The 'Birth of Radar' Memorial is located in a lovely little spot along the Northampton road

On the morning of the 26th, Watson-Watt arrived from London with the secretary of the Tizard Committee, A.P. Rowe and Watt's nephew Pat. They joined Wilkins at the site and settled themselves by the receiving equipment in the back of the van, whilst Pat and the van driver Dyer, owing to their lack of security clearance, made themselves scarce.

Shortly after their intended target, an RAF Handley Page Heyford Bomber (see my post about that here) piloted by Flight Lieutenant R. S. Blucke, flew over the site and along the path of the strongest signals from the radio tower. On the first attempt the bomber flew slightly off course and no variation was seen in the receiving equipment, but on the second attempt the line of the cathode ray tube fluctuated up and down - indicating a variance in the signal and that the Heyford had been seen - RADAR had been born!

Excited by the results of the experiment, Watt and Rowe then headed immediately back to London, leaving Pat behind for the night. Wilkins and Dyer packed up and followed later.

A Handley-Page Heyford, the type used in the experiment

The success of this experiment paved the way for the development of the 20 radar stations built around the coast of Britain ready for the outbreak of war in 1939. These stations played a vital part of the Battle of Britain in 1940 without which, the hard pressed Fighter squadrons of the RAF would have been stretched too thinly and, with invasion looming, the outcome of the Battle - and the war - could have been very different indeed.

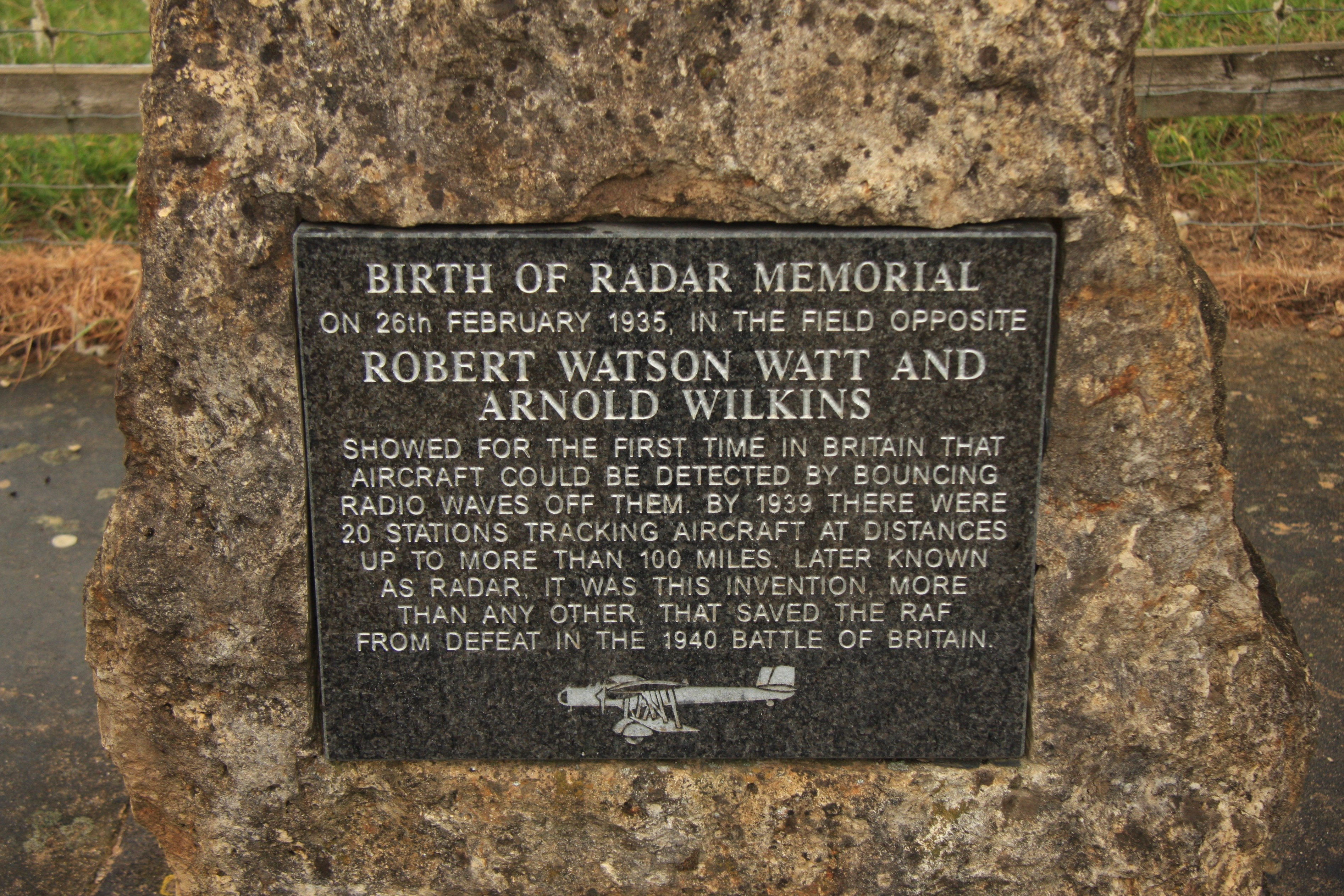

As an epilogue, In the late 90's Rex Boys - a former Daventry student, decided that such a momentous event deserved to be marked and it was thanks to his efforts that the memorial was erected on this site in 2001. Funded by QinetiQ, it was unveiled in front of a crowd of some 80 people from the Radar world by Wilkin's widow, Nancy.

The Memorial Plaque

So the next time you drink a toast to 'The Few', why not spare a thought and a glass for the Scientists that also helped in the defence of our country in its darkest hours.

The field opposite the memorial where the experiment took place

As I said, it's amazing what you can find by the side of the road.

Farewell my Friends.

Comments

Post a Comment